Rene Descartes

"Cogito Ergo Sum"

Descartes is famous for his "cogito, ergo sum," meaning "I think, therefore I am." This identified the "real" part of the self as the mind and not the body. The body, for Descartes, is a mechanism controlled by the mind. Descartes had a strange idea that the mind was connected to the body by the "pineal" gland in our body. The "mind" for Descartes is also related to what we might call "soul" to use more theological term (its important to note that Descartes is not an atheist and has involved "proofs" for the existence of God based on his philosophy).

For our purposes, we need to realize that for a strict Cartesian the body is part of the world which are "objects" and we, as thinkers, are "subjects." I mentioned the correspondence theory of truth, which means that we need to attach ideas that we have "in our minds" to objective reality "out there." Descartes was a rationalist which means that we did not get our "ideas" from the external world. Rather, our ideas come from our reason.

Edmund Husserl and Phenomenology

Edmund Husserl was a German philosopher responsible for the philosophical movement phenomenology. The Stanford Encyclopedia of philosophy defines phenomenology as

"the study of structures of consciousness as experienced from the first-person point of view. The central structure of an experience is its intentionality, its being directed toward something, as it is an experience of or about some object. An experience is directed toward an object by virtue of its content or meaning (which represents the object) together with appropriate enabling conditions." (see above link)

For our purposes, we need to note that phenomenology tries to understand the mind and the body (and the world) for that matter as inextricably intertwined with one another. We are embodied beings and what we called the "world" is not some objective reality "out there" but is created through our experience of the "phenomenon of the world." In contrast, Descartes believed that the mind could be "disembodied" and it would still constitute a subject. Phenomenology led to Sartrean Existential Phenomenology, a major influence on Paulo Freire.

"Intentionality": "The central structure of an experience is its intentionality, the way it is directed through its content or meaning toward a certain object in the world."

| ||

| Heidegger |

Heidegger, Sartre, and Existentialism'

|

| Jean-Paul Sartre |

Existentialism is a difficult term to define. As I said in class, we could define it along with Sartre as "Existence Precedes Essence." Or, we could, along with the Stanford Encyclopedia designate it as "“Existentialism”, therefore, may be defined as the philosophical theory which holds that a further set of categories, governed by the norm of authenticity, is necessary to grasp human existence."

However, I would prefer to look at some of the basic ideas/revolutions in thinking of two major thinkers: Jean-Paul Sartre and Martin Heidegger

Heidegger

If we remember from above, Husserl claimed that we "intend toward objects" in the world based on the meaning they have for us. Existentialism is a philosophy that speaks about the meaning of human existence and not merely the "fact" of it. As Freire writes, the "Banking concept" does not take into account the meaning of information:

"The outstanding characteristic of this narrative education, then, is the sonority of words, not their transforming power [. . .] the student records, memorizes, and repeats these phrases without perceiving what four times four really means or realizing the true significance of 'capital' in the affirmation 'the capital of Para is Belem" (Freire 318).

A very basic way to understand Heidegger's revolution in thinking is that he thinks about objects as intended objects and affirms that this is the more "essential" way we relate to the world. In other words, we relate to the world not in terms of objects "facts" but what we do with the objects and others that surround us.

The famous example is a hammer. We orient ourselves toward the hammer in order to, for instance, hammer in a nail. We do not see the hammer as an indifferent object, we see it as a tool for use. Heidegger calls this "ready-to-hand" rather than "present-at-hand." Heidegger argues that this is the first way we are in the world. The world is meaningful for us we do not "add" meaning onto an object (as if it were a "quality" added to a "substance").

The "world" is not an objective existence "out there" but rather something formed out of language and meaning. Without man (what Heidegger calls Dasein) there is not world (see Freire pg 325).

Sartre

Sartre's mantra is about human action tranforming the world. We are both "free possibility" and what he calls "facticity." Drawing on Heidegger, we are both "free" and situated. We have many possibilities but we are located in a history (individual and collective). Thus, the situation calls for action from the human subject. For Sartre, the world challenges us to respond and it is only by this response that we in turn act on the world and become.

The relevant idea in Sartre is that if we think that we are "completely free" or "completely determined" we are in what he calls "bad faith." Sartre offers some very concrete examples of what it means to be in "bad faith"

"Sartre cites a café waiter, whose movements and conversation are a little too "waiter-esque". His voice oozes with an eagerness to please; he carries food rigidly and ostentatiously. His exaggerated behaviour illustrates that he is play acting as a waiter, as an object in the world: an automaton whose essence is to be a waiter. But that he is obviously acting belies that he is aware that he is not (merely) a waiter, but is rather consciously deceiving himself.[1]

Another of Sartre’s examples involves a young woman on a first date. She ignores the obvious sexual implications of her date's compliments to her physical appearance, but accepts them instead as words directed at her as a human consciousness. As he takes her hand, she lets it rest indifferently in his, refusing either to return the gesture or to rebuke it. Thus she delays the moment when she must choose either to acknowledge and reject his advances, or submit to them. She conveniently considers her hand only a thing in the world, and his compliments as unrelated to her body, playing on her dual human reality as a physical being, and as a consciousness separate and free from this physicality.[2]

Sartre tells us that by acting in bad faith, the waiter and the woman are denying their own freedom, but actively using this freedom itself. They manifestly know they are free but do not acknowledge it. Bad faith is paradoxical in this regard: when acting in bad faith, a person is both aware and, in a sense, unaware that they are free." (from wikipedia)

Applied to Freire and education, if we believe that our students are "passive" we deny their ability to act freely and transform the world. However, at the same time we have to be aware that each student is coming from their own history and facticity. To quote from Freire:

Accordingly, the point of departure must always be with men and women in the 'here and now', which constitutes the situation within which they are submerged, from which they emerge, and in which they intervene. Only by starting from this situation--which determines their perception of it--can they begin to move. To do this authentically they must perceive their state not as fated and unalterable, but merely as limiting--and therefore challenging (Freire 327)

It is here where Freire begins to define "problem poses education as the "problem of situation." By becoming aware of their situation (coming to consciousness as a class or even as an individual) students are able to realize that the very (historical) situation they find themselves within is a "problem" to be questioned and one to be acted upon.

Hegel and Marx: Transforming History

|

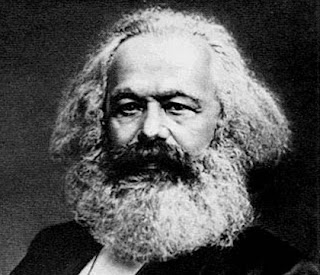

| Karl Marx |

| ||

| G.W.F. Hegel |

Marx worked out of the tradition of Hegel, a prolific philosopher who basically thought he had accounted for all of history and human thought. Anyone working in the tradition of "continental philosophy" nowadays is working both with and against Hegel (he is a figure to be reckoned with).

In "The Banking Concept," Freire refers to not Hegel's theory of history (which I very very quickly explained in class today), but Hegel's "master-slave dialectic": "The students, alienated like the slave in the Hegelian dialectic accept their ignorance as justifying the teacher's existence--but, unlike the slave, they never discover that they educate the teacher" (319). The master-slave dialectic recognizes that the relationship between master and slave is complicated because the master, in order to be a master "needs" the slave (or else, he would not be a master). This example is much more complicated than this, so I refer the interested reader to the wikipedia page for more elaboration.

Marx

Marx wrote in his Theses on Feuerbach, "The philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways; the point is to change it."

Indeed, the whole text of the "Theses" is about moving from description of the world to transforming the world as Freire writes in his text:

The world--no longer something to be described with deceptive words--becomes the object of that transforming action by men and women which results in their humanization. (328)This is basically what Marx/Freire means by praxis--human action and theory are inevitably intertwined. Theorizing about the world is also acting in the world.

We act in the world and try and transform the world in order to overcome alienation. While "alienation" has some everyday language connotations, Marx is talking about a specific form of alienation--alienation of labor:

It is important to understand that for Marx alienation is not merely a matter of subjective feeling, or confusion. The bridge between Marx's early analysis of alienation and his later social theory is the idea that the alienated individual is ‘a plaything of alien forces’, albeit alien forces which are themselves a product of human action. In our daily lives we take decisions that have unintended consequences, which then combine to create large-scale social forces which may have an utterly unpredicted effect. In Marx's view the institutions of capitalism — themselves the consequences of human behaviour — come back to structure our future behaviour, determining the possibilities of our action. (from Stanford Enyclopedia entry on Marx)

Thus, just as we are alienated from our labor in Marx, so Freire argues that we are alienated from our own education. What is the consequence of this? The Banking Concept of Education.

Conclusion

I hope I have shown both in and out of class the complex history and background of Freire's thought. It is not merely an exploration of the classroom situation, but the very idea of education and its relation to authority, power, subjectivity, freedom, possibility, and revolution. It is philosophically grounded in Marxist, Existentialist, and Phenomenological thinking.

Despite having spent about an hour on this post, I have only scratched the tip of the iceberg of these thinkers. Without the texts of these philosophers before me, I feel like I have done them a disservice in my explanations, but we have to start somewhere.

No comments:

Post a Comment